Cha chronicles her life and the historical context of the era, including quotes from her and historical documents, such as a letter to President Roosevelt. She died from being tortured by military police following her involvement in student protests in the famous March 1 movement and became a national hero. In “Clio History,” Cha explores the life of Yu Guan Soon, a Korean woman who died in 1920 at the age of 17 due to rebellion against Japanese imperial rule in Korea in the early-20th century. The child struggles through the rituals of her religious school and feels deeply alienated by the culture of Christianity. In “Diseuse,” Cha introduces the narrator, who is a close representation of herself: a girl learning French and English and struggling with the fear of speaking in an unfamiliar language. Cha leads readers to question their assumptions about power, gender, national and ethnic identity, and language.

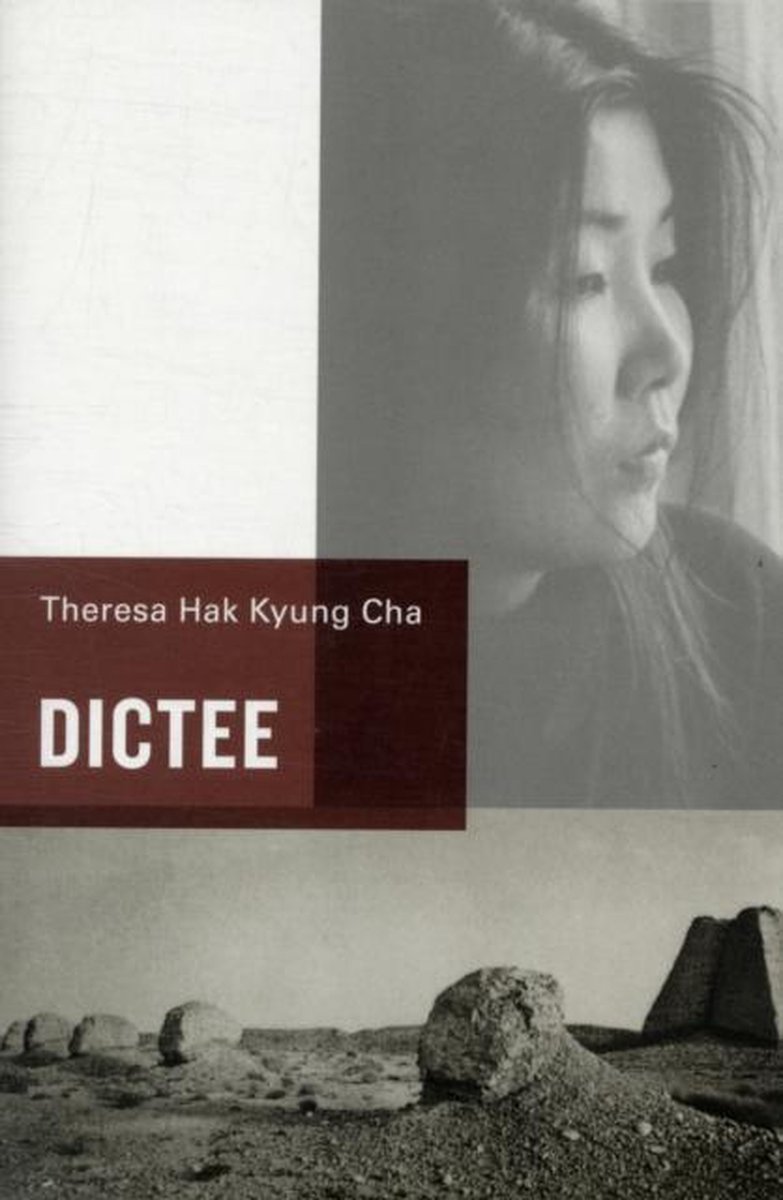

Defamiliarization, or the process of making familiar objects strange, allows Cha to penetrate the tropes and cliches of memoir, historical representations of Korean history, and mythology. Using experimental and post-modernist literary and artistic techniques, Cha uses uncaptioned photos, untranslated French, Korean, and Chinese text, and other means of defamiliarizing the contents of the book.

However, the contents of the chapters oftentimes subvert the expectations that the chapter titles set: “Thalia Comedy” is not humorous but instead features a series of jumping scenes between a woman in a theater, letters to a mysterious woman named Laura Claxton, and poems about the goddess Persephone, Demeter’s daughter. Each chapter is titled after one of the nine classical muses, the daughters of Zeus who each ruled over a different category of art or science. The women are martyrs, saints, sinners, and goddesses who rebel against their societies, with different results.

In each chapter, Cha explores the lives of women under systems of colonial rule and other forms of oppressive governance. Cha explores the concepts of colonialism, martyrdom, the experiences of women, and art. Referring to Cha’s life first as a Korean child living in China, then as an émigré in the United States learning English and French in Catholic school, the title is symbolic of Cha’s wish to escape from the history of trauma, war, and exile that defines her mother’s and her own life and create a new language which is not merely a repetition, but rather something new that is reflective of a more authentic social reality. The book’s title, Dictee, means “dictation” in French, and this word becomes infused with irony as the book progresses.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)